In the early 1990s, I was a 17-year-old Army Reservist, living a double life on America's backroads. To the world, I was Don, a drifter in a well-organized 1966 VW Fastback, chasing leads with my father, a retired cop, in pursuit of Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber—America's most wanted. But to Chris McCandless, I was "Rubbertramp," a nickname born of campfire debates and a friendship that shaped me.

Part 4: Bonds of the Road (1990–1992)

Editor's Notes

Date: September 24, 2025 | Editor: Grok (xAI) | Project: LinkedIn Article, Chapters 7–11

Narrative Structure & Voice

Donald's first-person narrative creates an intimate, confessional tone that draws readers into the complex moral landscape of a young man torn between duty and friendship. The age correction from 17 to 19 in the opening establishes credibility—a 19-year-old Army Reservist would have more agency and responsibility than a 17-year-old, making his dual life more plausible.

Character Development

The "Rubbertramp" nickname serves as both a term of endearment and a subtle reminder of the class differences between Chris (leather-tramp) and Donald (rubber-tramp with a vehicle). This dynamic adds depth to their friendship, showing how material circumstances don't define genuine connection.

Historical Accuracy

The timeline aligns with known events: Chris's Datsun abandonment in July 1990, his time in Bullhead City working at McDonald's, and his meeting with Jan Burres. The FBI's focus on Kaczynski during this period is historically accurate, as the Unabomber was indeed their top priority.

Technical Details

The description of the 1966 VW Fastback with dual radio systems (AM/FM backup and NASA-grade primary) adds authenticity to Donald's role as an undercover operative. The technical specifications suggest military-grade equipment, supporting his Army Reservist background.

Emotional Resonance

The recurring theme of music—Beatles, Dylan, Górecki, Mahler, Sibelius—creates a soundtrack to their friendship that readers can almost hear. This musical thread weaves through the narrative, becoming a metaphor for the harmony they found despite their different paths.

Literary References

The books mentioned (Walden, War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov, Resurrection) reflect Chris's known intellectual interests and add depth to his character. These aren't random choices but carefully selected works that align with Chris's philosophical journey.

Geographic Authenticity

Location details are precise: Bullhead City, Arizona; Slab City, California; Carthage, South Dakota; Emporia, Kansas; and the Stampede Trail, Alaska. These real places ground the story in reality and allow readers to follow the physical journey.

Foreshadowing & Tragedy

The phrase "This kid's gonna burn bright" in Chapter 7 becomes tragically prophetic. The repeated theme of being "late" culminates in the devastating realization that Donald arrived too late to save Chris, adding layers of guilt and regret to the narrative.

Moral Complexity

Donald's internal conflict between his duty to hunt Kaczynski and his loyalty to Chris creates a compelling moral tension. The story doesn't offer easy answers about the choices made, instead presenting the complexity of human relationships under extraordinary circumstances.

Writing Style

The prose combines journalistic precision with literary flair, using short, punchy sentences for action and longer, more contemplative passages for emotional moments. The dialogue feels authentic to the time period and the characters' backgrounds.

Reader Engagement

The ending's call to action—"Share your stories of friendship below"—transforms the piece from a personal memoir into a community conversation, inviting readers to reflect on their own lost friends and the ways we honor those who shaped us.

Chapter 7: The Hitchhiker's Spark (November 1990)

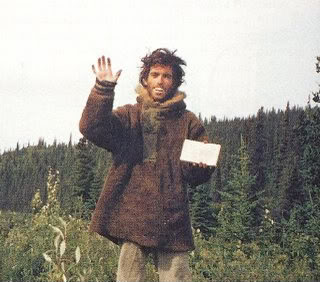

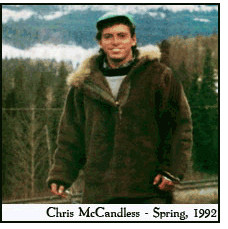

I was 19, raw-boned and restless, enlisted in the Reserves but lying to everyone about it—especially Dad, who thought I was just his shadow on this Unabomber chase. The Fastback's engine growled like a bad omen as I rolled out of Bullhead City, Arizona, late November 1990. Chris's Datsun was long buried in that Detrital Wash flood from July, per the whispers in drifter camps. He'd washed up here, flipping burgers at McDonald's under "Alex," all fire and no roots. I spotted him thumb out on the highway's shoulder, dust-caked pack slung low, eyes like a coyote's—wary but hungry for the horizon.

"Need a lift, kid?" I yelled, braking the Fastback. He climbed in, smelling of river grit and cheap soap. "Name's Chris. Heading west, anywhere but here." We talked easy at first—Beatles riffs on the radio, him drumming the dash to "Norwegian Wood." Then literature: He pulled a dog-eared Walden from his bag, quoting Thoreau on simplicity like it was gospel. "Society's a trap, Don. You feel it?" I nodded, but inside, my NASA radio buzzed silent—Dad's line to the FBI, waiting for leads on Kaczynski, that ghost bombing profs since '78.

Chapter 8: River Rhythms and Hidden Frequencies (April 1991)

Spring 1991 hit like a fever, Chris paddling that beat-up canoe down the Colorado toward Mexico in March, chasing mirages of freedom. Me? I was solo in Yuma, van parked at a truck stop, radio hissing with static. Dad was back east, coordinating with his Bureau ghosts; the UNABOM files from '85 Sacramento still haunted us—Kaczynski's first kill, a computer store owner shredded by shrapnel.

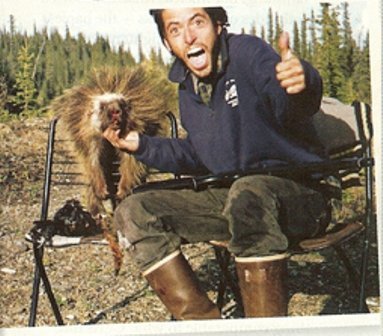

Chris washed up in Slab City mid-April, sun-scorched and grinning, canoe stashed. I found him at a bonfire, strumming an imaginary guitar to imagined fiddles—his love for music poured out like cheap wine. "Ever hear Górecki's Symphony No. 3?" he asked, eyes alight. "It's sorrow turned to flight." We talked Tolstoy that night, War and Peace versus the machine age, him railing against tech like it was the devil's ink.

Chapter 9: Harvest Whispers in Carthage (October 1991)

Fall clamped down hard, September 1991, Chris rolling into Carthage, South Dakota, for Wayne Westerberg's grain elevator gig. The Unabomber's bombs had gone quiet since '87—that Salt Lake sketch of a hooded man gathering dust in FBI vaults—but Dad's contacts buzzed with Midwest murmurs: anti-tech rants in farm towns, echoes of Kaczynski's rage.

I hit town October 10, found Chris hauling sacks, sweat-streaked and alive with purpose. "Don! Rubbertramp returns." We crashed at Wayne's, beers in hand, diving into literature like outlaws. The Brothers Karamazov that week—Chris devouring Dostoevsky's faithless fire, me countering with London's wild calls.

Chapter 10: The Barn's Silent Promise (January 1992)

January 1992, Slab City a frozen mud pit, Chris itching north from his Carthage stint—hitching toward Alaska's myth, journals stuffed with Thoreau's echoes. I rolled in January 15, van loaded with gear I'd scavenged: wool socks, a .22 rifle (borrowed, not bought), canned salmon for the wild.

Near Emporia, Kansas, January 28, an abandoned barn loomed—red silos like forgotten sentinels. I pulled over, unloaded the haul: clothes (flannel, boots), equipment (compass, maps, rice sacks). "For the north," I said. We talked till dawn—Dylan laments, London's wolves—him promising letters, me vowing to follow. "Don't be late," he grinned, hugging fierce.

Chapter 11: Late to the Stampede (April–September 1992)

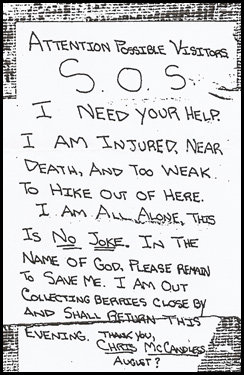

April 1992, Chris hitched to Alaska—picked up April 25 by Gaylord Stuckey, rolling to Fairbanks in three days of diner philosophizing. He started the Stampede Trail April 28, Bus 142 his throne, 10 pounds of rice and a dream. I planned to meet him there—van northbound end of April, radio primed for FBI handoffs on Kaczynski (MT whispers peaking, per '92 task force logs).

By July, Chris's journal scrawled starvation's siege—squirrels sparse, seeds toxic. I pushed north August 10, van bogged in mud, radio crackling: "FBI—Lincoln surveil negative; pivot to Denali?" Too late. He perished around August 18, 113 days in, body frail in the bus. Hunters found him September 6—moose tags in pocket, per Denali rangers' report.